For Grammy

Death reminds us that we are children. For those of us who live into old age, death returns us to a state of frailty and dependence. For anyone who believes in God, this would seem to be perfectly intentional. We enter this world utterly dependent, and we leave this world critically aware of exactly how little lies within our control.

From this perspective, physical strength, emotional endurance, and adult agency would seem to be mere illusions. The idea that we actually understand or control anything is borderline laughable. But health and age—during that limited intersection when we seem to have both things at once—allow us to live the dream… at least for a little bit.

The reality is that we are helpless to stop or change most things. The reality is that anything beyond our own personal scope of thought and action is completely out of our control, despite our bitter attempts to assert dominance. This is probably why free will and moral culpability matter so much; they are all we really have.

Of course, despite the many similarities between the very young and the very old, the very old leave this world riddled with acute memories of the manifest fruits and famines caused by their exercise of moral agency. The young cannot understand this, or at least cannot understand in the way we understand understanding.

Mothers are granted the dubious gift of being able to access both the beginning and the end of life in the act of childbirth. In bringing a child into this world, most mothers are brought closer to their own deaths than they have ever been before. To bring life into existence, they have to taste death. They have to suffer until they taste despair. They have to be broken until they can be reshaped. They have to die to themselves to be reborn as the mother of their children.

Gabriella’s birth brought me to despair. There was so much pain and so much exhaustion that I could do nothing but sob without breathing multiple times throughout my labor. My midwives sat with me, held my hands, and gently reminded me that I cannot change my child’s story; this was her birth and her journey. I lived each step of it with her, and it shaped and defined us both—irrevocably.

I think death must be similar. I think the physical pain continues to mount until you feel you can no longer withstand it; then, you find deeper reserves of endurance and strength that you didn’t know existed. In childbirth, there is no other way out but through. I think death is the same. There is no end to the pain until your heart and lungs stop. The strength required to get to that point is unspeakable—unimaginable—impossible…until you are forced to find it.

The dying appear both fragile and dependent. From the outside, the suffering is all we can see. We cannot see the internal battleground, the profound courage, or the excruciating compulsion of will to endure and endure and endure until the end. We know enough to say, “At least now she’s at peace,” or “her suffering is finally over,” but this itself is a kind of grasping at hope. The oppressive inexorability of death is still too close. It causes us to cry and pray and buy flowers. It makes us want to be held, to eat, and to sleep.

It reminds us that we are children.

So, is that it? Is God just this malevolent and obscene Destroyer—the biggest bully who will always win in the end by being darker and more immutable than anyone and anything else? I don’t necessarily blame those who come to this conclusion. They usually arrive there because they have seen too much of death and pain—too much for any mortal brain to endure.

But it may also be the coward’s conclusion and one I can only feel ends in suicide. Because of this, I’ve chosen to believe that there is a deeper magic at play–a magic that existed before the dawn of time.

Our culture sees death as something to avoid; beyond the funeral and the burial, we don’t like to talk about it or about the many ways grief continues to bleed out weeks and months and years after the grass has covered the newly dug grave. Our culture likes to mock and flirt with death, so we place plastic skeletons in our front yards every October. We try very hard to ignore that death doesn’t happen only to the very old or to the soldiers who signed up for it.

This is because when it happens to us or to someone close to us, we are brought to our knees by its proximity and its imminence. There is no fighting it and no undoing it. There is shaking and shock and intestines writhing like snakes. There are throats sore from screaming, bloodshot eyes, and the need to hide until it’s all over. There is wordlessly shaking your head and soundlessly sobbing as you realize there is nowhere to hide, and it will never be over.

The deaths of those we love force us to face these realities—to acknowledge our own frailty and dependence and lack of control. I can only imagine that our own deaths place us intimately and unavoidably face-to-face with our identities as children. And I suspect that death—like birth—only comes at the moment that we finally surrender to that reality.

Eight days ago, my grandmother died in her sleep at the age of 93. Unlike her husband’s death 9 years earlier, we did not witness it. We hope it was peaceful, but that could be part of the fantasy. Only she and God knows exactly how hard it was for her and exactly how long it took her to surrender herself as His child.

Her funeral was yesterday. Her coffin was open before the service. I placed my warm hand over her cold one and pressed my warm lips to the place where her brow meets her hair. Her face was sunken and looked so little like the grandmother I have known and loved all my life. Memories of her laughing or bouncing up and down as she spoke emphatically kept flitting through my head like fireflies searching for a place to hide. The body in front of me was not Grammy; it was the physical substance she left behind. But it mattered when she dwelled within it, and it still matters now… because without it, she never would have been.

I have not seen or touched a dead body since Lizzy. The horror of seeing Lizzy’s dead body will stay with me for the rest of my life, but it dims in comparison to the horror I would have felt had I never seen Lizzy’s dead body. Midwives say that the mothers who are never given a chance to see and hold their stillborn babies are always worse off than those that were. I think this is because the scope of human imagination is so dark and twisted that the truth–no matter how brutal–will always be cleaner than invention.

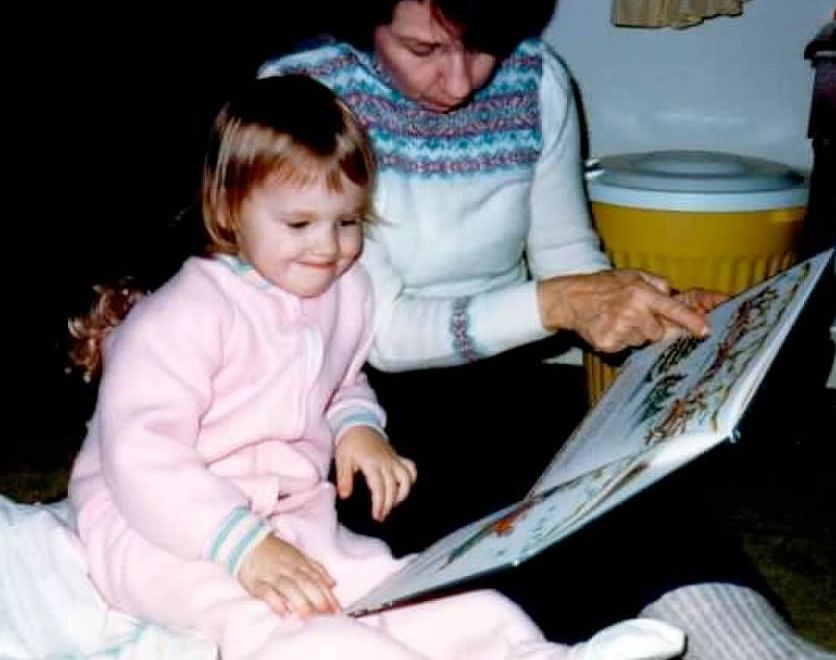

I could not accept the idea of hiding or turning away from the body of my daughter that I had carried inside my womb and nursed at my breast and held in my arms so I held her and kissed her cold brow and swallowed the agony of witnessing the damage done to her body in the process of trying to keep her alive. I found I could not turn away from the body of my grandmother, who had held me in her lap and read me bedtime stories and hugged me with all of her strength when I returned home from a semester abroad in Ireland.

I kissed the cold flesh of my grandfather, my grandmother, and my daughter. Once their coffins were closed, I kissed the cold wood of their coffins. Once their coffins were buried, I kissed the cold granite of their headstones. I do not blame those who will not or cannot do this. Everyone responds to death differently. For me, I believe that their bodies matter and what happens to their bodies after death matters. For me, the dignity and respect due to human flesh does not diminish when that flesh loses all warmth.

I will never be able to accept the need that people have to talk at funerals. Yesterday, everyone wanted to speak to me, and I wanted to speak to no one. In the face of death, silence is frightening. So people fill the silence with voices and questions and opinions, scurrying like mice under flashlights until they can find their way back to a nest.

It was worse when Lizzy died, and I had less strength to endure it. Everyone wanted to say something, to make it better, to fill the silence, to hide from their own horror and grief. Everyone had questions about how Lizzy died and theories about why she died. No one–including me–could acknowledge that the how and why are beyond human comprehension. Peter alone sank to one knee, took my hand, pressed it fiercely to his lips, and said not one word.

What do we do when words are clearly not enough? Before doctors and hospitals, a vigil was maintained over the sick and dying: a quiet continuum of silence, service, respect, and prayer. There was implicit acknowledgement that the dying were touching the world beyond the living–a place that we have no right to pretend we understand. Often, it was monks and nuns who performed these tasks, used as they were to fasting and silence and sorrow. The best midwives keep the same kind of vigils, remaining physically present but silent, allowing themselves to enter into a kind of meditation anchored by the groans of the laboring mother. They are the wordless keepers of an ancient mystery–a mystery too profound and primordial for mortal articulation.

We have forgotten how to be silent.

I wrote a eulogy for my grandmother. I wish that the words in my eulogy were the only words I spoke yesterday. I did not talk about how she died or how painful and lonely the past 9 years must have been for her. I tried to describe the beauty of my family and leave out the brokenness and pride. My grandparents helped make our childhood absolutely magical. They loved us, and we loved them. That’s what I want to remember.

I don’t want to remember the conversations I overheard yesterday as people milled uncomfortably about in front of Grammy’s open coffin. I don’t want to remember the conversations I overhead as I sat staring numbly at the open grave site. I don’t want to remember people walking without thinking over the grave of my daughter.

Without memory, we could not have relationships. But memory is two-edged, and I think part of growing up is choosing to remember the good and allow the bad to fade. The best way to accomplish this is to stop talking about it. The best way to shape a brain that can rouse from sleep in the mornings and not sink immediately into desolation is to think about the good. To expose that brain to as many things that are true and beautiful as possible and to turn away, again and again, from the dark and the ugly, the selfish and the shameless.

I am currently living through that dreamlike period in human life where I have both health and age. I can transition from sobbing for the deaths of my grandparents and the brokenness of my family to nursing my 10-month-old and adoring her starlit eyes and milky, mischievous grins. I can move from listening to strangers ask horrifying questions and make casual comments about Lizzy’s grave to listening to Cecilia tell me about the acorns she hears dropping onto our minivan.

I can go from the cemetery to the warm lights of my home, my children’s bedtime prayers, and the arms of my husband.

I was not given the opportunity to hold a vigil for my grandmother, but I held vigils for my grandfather and for my daughter. I will not hold onto the anger or disgust or regret that I feel. These things can only poison my children. Instead, I will teach them the things that my grandmother taught me and discipline them in the ways that my grandfather disciplined me. I will teach my children about silence, respect, and dignity in the face of death. And I will teach my children about death.

Children, more than adults, are able to understand that life is not within their control. Because of this, I believe that children can understand that death is something that requires absolute surrender of control. I believe this because I watched how Lizzy died. I watched her trusting, tiny face as they anesthetized her and I told her that I would be there when she woke up and explained how everything was going to be okay. It was not Lizzy who could not surrender to the imminence of her death. It was me.

I am terrified–terrified that my own death will be very long and very painful, mostly because my labors are very long and very painful. I take a very long time to surrender wholly to the pain of childbirth, and, in the process, I have very long and exhausting labors. I pray that in the time I have left between now and when I die, I will learn to surrender more to God and to my own mortality–to trust in my own lack of control. I pray that, by the time I die, I will be more prepared to be a child, and that this humility will not be forced on me by infirmity and incapacity.

I pray that I will trust God like Lizzy trusted me.

Death makes us all children. But only the dead remain children. The rest of us return to our dream fantasies of dominance and control and talking too much for all the wrong reasons. In trying to cope with my own grief, I have said too much and spent too little time in silence and in prayer. I can continue to write about how I need to become more childlike, or I can turn my attention to my children, who daily live the meaning of surrender.

Eight days ago, my grandmother died. Eight days ago, my grandmother died alone. I pray that this somehow made it easier–that it allowed her to leave her body and enter the arms of God with fewer people tying her to the physical world. I pray that I am not writing this statement only to help me feel better about her death.

There is too much suffering and death in this world. I refuse to consciously contribute to it. So I will write and speak about the beauty in the lives of my grandparents and the wonder they helped to create in our childhood. I will choose to remember them as they lived and allow the darkness of their deaths to fade. I will let the eulogy I spoke yesterday be the eulogy everyone remembers.

The rest is silence.

Eulogy for Grammy

October 5, 2023

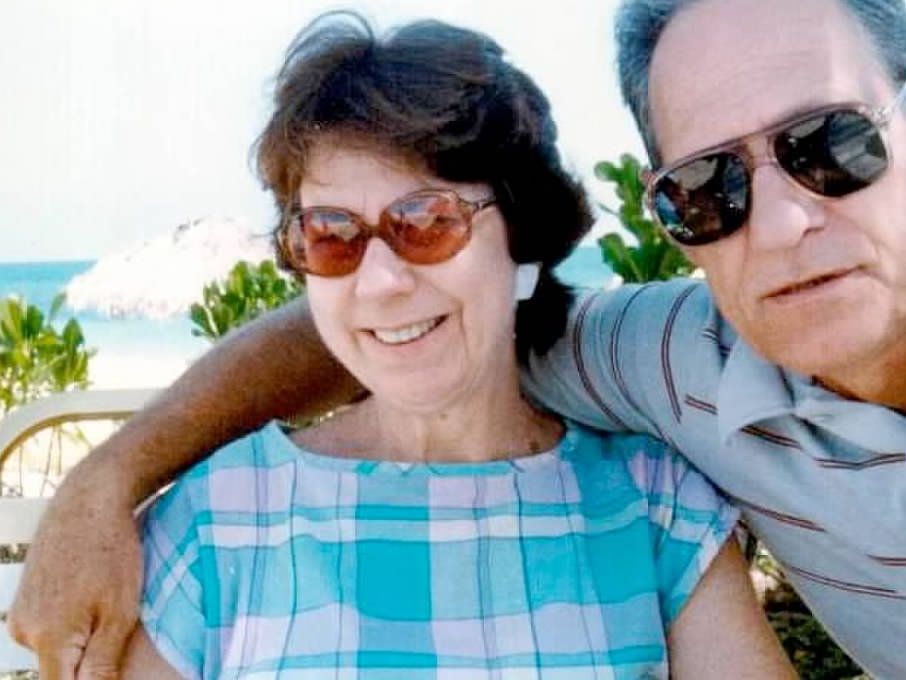

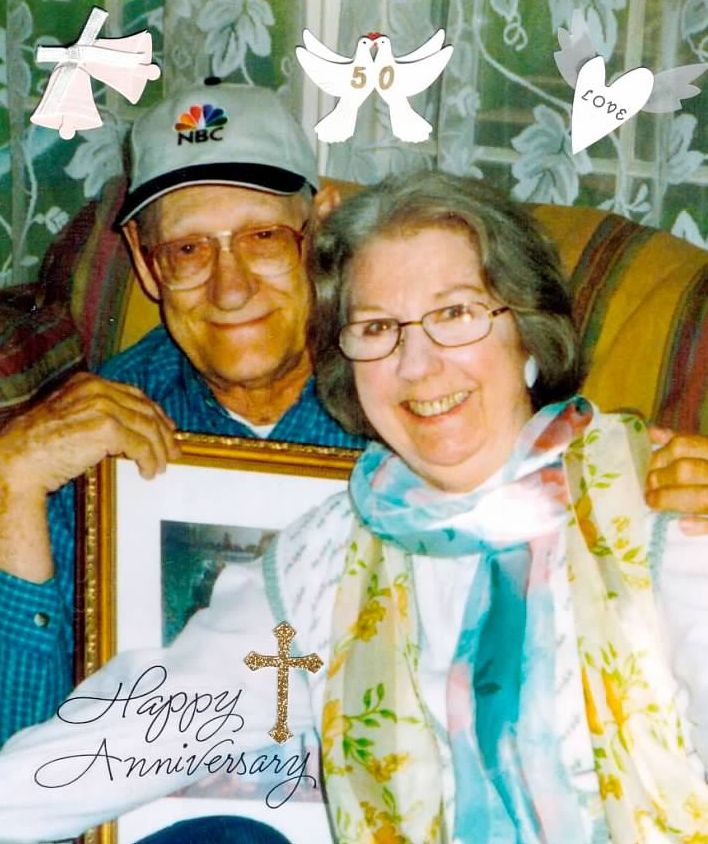

When my grandfather died, my grandmother walked around dazed, phasing in and out of reality. The bone of her bone, flesh of her flesh, and father of her children no longer ate and slept and prayed by her side. Or if he did, she could no longer reach out and grab his hand—just as wrinkled and spotted and weathered as her own—and feel she was not alone. For more than 60 years, they loved and suffered and raised their children together. When he died, she could no longer understand herself.

For the past 9 years, she has carried the burden of life without him. Their 3 children have witnessed this long and quiet martyrdom, held her trembling body as its frailty and dependence steadily increased, and listened as each word became more faltering and labored. For the past 9 years, my mother and aunt and uncle have carried this burden for their parents.

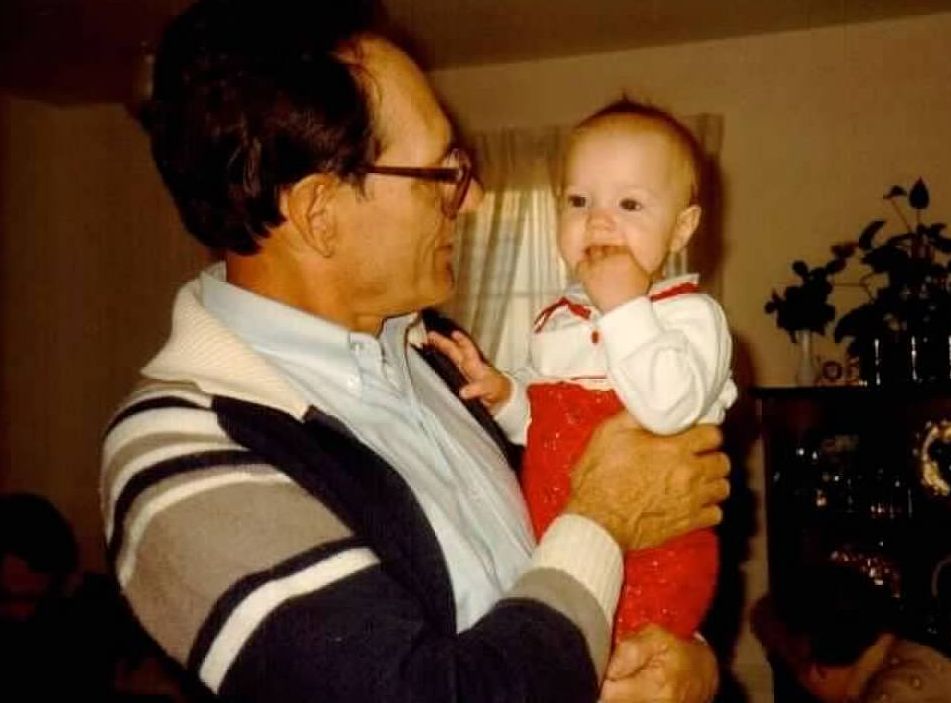

As grandchildren, we cannot think about Grammy without thinking about Grandy. I can close my eyes and see him standing a full foot taller than her, hand at her elbow, guiding her gently in and out of the car, over a slippery patch of turf, through a waltz at my sister’s wedding. Together, they walked and laughed and worked their way through our childhood, showing us without trying the kind of marriage we hoped one day to have.

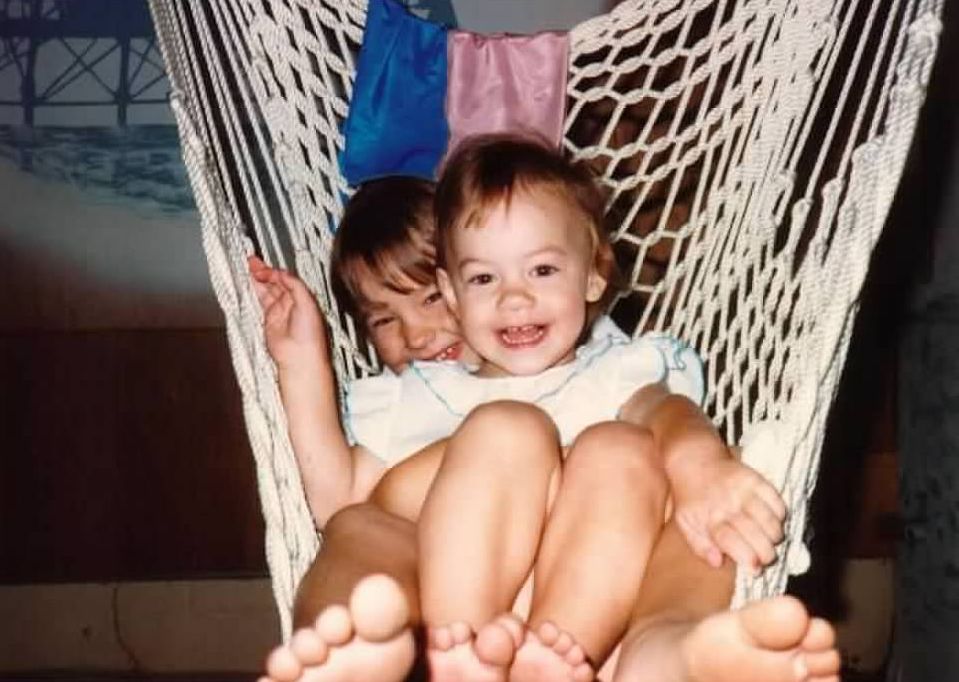

One white Christmas, Grandy built two beautiful sleighs, complete with jingle bells, and all seven of us were pulled—red-nosed and giggling—in snowy circles around their backyard. Later, Grammy helped us don our costumes and memorize our lines for our annual nativity pageant, then clapped louder than anyone else at our stumbling performances. After the festivities, we sat on laps and sucked on candy canes as handmade stockings were distributed from the groaning mantelpiece, one by one.

In the fall, Grandy taught us how to rake leaves and dig for potatoes, while Grammy sat us in front of the spice cabinet to sample the aromas of cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, and ginger. As a rite of passage on Thanksgiving, Grandy showed us how to eat raw oysters doused in cocktail sauce, then rush outside to breathe in the smell of the bay on the crisp, autumn air.

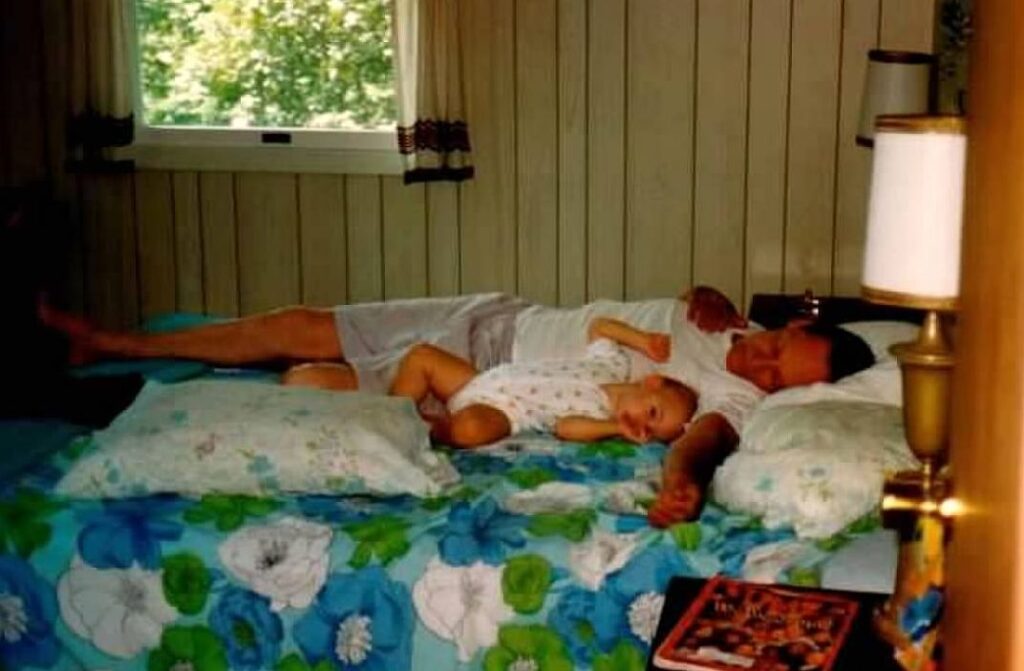

Our summers were spent at Grammy and Grandy’s tiny cottage on the Chesapeake Bay, dipping for crabs and plucking ripe wineberries from the brambles. My early mornings were spent on the cottage couch with Grammy, sifting eagerly through her shoebox filled with arts and crafts and smelling Grandy slow-cooking bacon and buckwheat pancakes on the griddle. After breezy days spent tracking ospreys and exploring the tides, we made sandwiches from dripping, sun-ripened tomatoes and danced with Grammy to Harry Belafonte’s “Hava Nagila.”

Every Wednesday during the school year, I slept over at Grammy and Grandy’s house after Grandy took me to my violin lesson. Sometimes, Grammy spent endless hours helping me learn how to read, spell, and edit the children’s stories I could not stop attempting to write. Sometimes, Grandy would teach me how to mow the lawn or shoot a basket or trace a perfect line using his shadow box. And then we would eat rotisserie chicken and read The Gunniwolf and recite the Guardian Angel Prayer as they tucked me into bed.

Grammy and Grandy were present to cheer at our basketball games and cry at our graduations. In the moments when we could have been kinder or made a better decision, Grandy would speak to us privately and share a story from his life when he had faced a similar situation. When we found ourselves obsessed with music or movies that were somewhat less than wholesome, Grammy engaged us with the Socratic method, inviting us, without criticism, to examine our choices.

They never had to try to present a united front; their unity as husband and wife, father and mother, grandfather and grandmother was effortless and unquestioned. Together, they shaped and guided our family, constantly modeling the behavior they requested from us. They lived with grace and integrity, teaching with action what it means to give your life in service to your spouse and your children. And, despite the divorce of Grammy’s parents when she was 5 and the death of Grandy’s brother in Iwo Jima, they lived with faith and humility, teaching with silence what it means to believe.

That faith anchored Grammy when Grandy died. It anchored her again when my first daughter, Elizabeth, died 16 days after her 2nd birthday. After Lizzy’s funeral, Grammy sat with me, her face radiant despite the tears coursing down her cheeks. She took my hand, her skin soft and nearly translucent, and squeezed it as hard as she could. Laughing through her tears, she repeated, “We have a family saint! We have a family saint!”

Since Lizzy’s death, people have asked me how I can still believe in God. My answer is that I believe my daughter is not gone because she is no longer in her body. I believe that there was no place for Lizzy to go except to heaven. I believe in a God who gave Himself up to suffering and despair to ensure that death would not be the end of the human story. I believe in my second daughter, Cecilia, who lived through Lizzy’s death with me when she was 8 months in utero. I believe in my husband, Peter, who is my lived reality of everything I have ever dreamed of or hoped for from marriage. And I believe in my third daughter, Gabriella, who, with her birth, brought me joy I thought I would never know again.

My daughter, Elizabeth Aviva Fiada, only lived for 2 years, but the perfect wonder and beauty of her life cannot be undone by her death or the brevity of her life. My grandmother, Marie Elizabeth, lived for 93 years and died a beloved wife and mother, a cherished grandmother and great-grandmother. Either their deaths are the beginning of a winter that never ends, or Good Friday and Holy Saturday give way to the dawn of Easter Sunday.

Lizzy was born on the first day of spring and died when the cherry trees and daffodils were in full bloom. I named her “Aviva,” Hebrew for spring. Gabriella was born on December 8, the feast day of the Immaculate Conception, 2 days after the birthday of her great-grandmother. I named her Evangeline, for her birth brought me tidings of great joy. Lizzy’s body is buried next to Grandy’s, whose headstone has sat with Grammy’s name and birthday carved next to his for the past 9 years. Now, Grammy’s body will lie next to the bone of her bones and the flesh of her flesh, together in death as they were in life.

I have no words to thank them for the example that they provided or the hope that they offered. I have only the prayer that, at the moment of her death, Grammy found herself walking on a carpet of clover down rivers of sunlight to find my little saint of the springtime planting daffodils with her great-grandfather in a garden that never dies.