Cicada Summer

Dear Lizzy,

It has taken me several weeks to work up the courage to write this letter, and it has proved even harder than I feared. I have been comparing Cecilia with you since she was born and even more so upon learning of her diagnosis. I have been trying to replicate experiences which you and I shared, vainly attempting to recover something of how very much was lost when I lost you.

You turned one on March 20, 2018, and the summer that you were 15-18 months old was the happiest of my life. We spent that summer travelling, laughing, exploring the world, and loving one another. Your little sister was conceived that July, but I didn’t know until August. Back then, you were my everything, and the whole world lay open before us.

Cecilia turned one on May 5, 2020, and I hoped for a duplicate experience of our 2018 summer together. The pandemic travel restrictions, however, eliminated that hope, but the truth is that Cecilia was not physically or developmentally ready to travel and experience new places. Instead, I patiently watched her grow and work so hard to accomplish the milestones that came so easily to you.

Lizzy and I at Polyface Farms in Swoope, VA, July 2018

Cece and I at The Family Cow in Chambersburg, PA on Cece’s second birthday, May 5, 2021

This summer marked the emergence of the 17-year cicadas, and Cecilia’s birthday was heralded by a deafening chorus dominating the outdoors. At times, the noise seemed to penetrate the walls, and the disheartening sight of dead cicadas scattering the front stoop greeted our attempts to check on the garden. On our bike rides, cicadas bounced like acorns off of helmets and shins. Daily dialogue was buffeted by the endless repetition of the cicadas’ song, and sometimes, it became difficult to even hear yourself think.

Somewhere around July, the noise stopped. Dead cicadas crunched underneath car wheels, and the trees were littered with webbed cicada nests that had killed the tips of the branches and would eventually break and drop to the ground so that the eggs could return to their underground domain. After so much noise for so long, the silence seemed uncanny.

I hope to never experience a worse summer than those desperate months after your death, but I think this has been one of the hardest summers of my life. I have become lost in the labyrinthine bowels of family relationships and spent long hours locked in the stifling cellars of the human heart. The broken relationships and painful exchanges of these summer days found their zenith in the death of your great-grandfather and the consequent grief it brought to your grandfather. After death generally, and especially after a death like yours, you tend to believe that some things should be very simple from now on–indefinitely. But humans know how to complicate life, love, and death alike, and I find my ability to trust is growing more and more compromised with time.

Still, through this pain, there has been Cecilia. Her second birthday marked a rebirth for my heart, and once we reached seventeen days past May 5, I made a decision to stop being afraid and follow you–to follow the way that you pursued every experience, went after everything that life had to offer you, and explored fearlessly and wondrously. So that’s what we’ve done this summer, Lizzy. We’ve tried to be like you.

We’ve gone on countless bike rides in your bike seat and helmet.

Lizzy

Cece

I’ve taken Cece on short cruises, remembering your face smiling in the light reflecting off the water.

Lizzy on a shelling cruise, August 2018

Cece on a sunset cruise, July 2021

We’ve planted and discovered gardens together, immersing ourselves in the world of living things.

Lizzy exploring a friend’s farm in June 2018

Cece garden surfing in June 2021

She shares your curiosity and thirst for exploration, although she’s more content to just sit and absorb the world around her.

Lizzy petting a goat at White Oak Lavender Farm in Harrisonburg, VA, July 2018

Cece laughing at Meadowlark Botanical Gardens in Vienna, VA, July 2021

Lizzy exploring the gardens of White Oak Lavender Farm, Harrisonburg, VA, July 2018

Cece exploring the Children’s Tea Garden at Meadowlark Botanical Gardens in Vienna, VA, July 2021

We’ve visited turtles, sting rays, and farm animals. She loves mimicking the sounds they make or staring into the mesmerizing abyss of blue water, but she doesn’t yet have your insatiable love for all God’s creatures.

Lizzy at the Mote Aquarium in Sarasota, FL

September 2018

Cece at the Calvert Marine Museum

in Solomons, MD, August 2021

However, we did have a nice visit with baby chicks, and she’s finally learning how to pet dogs with the same gentleness that came so naturally to you.

Lizzy petting a baby chick, July 2018

Cece clapping for a baby chick, April 2021

Lizzy communing with a bunny at Polyface Farm

in Swoope, VA, July 2018

Cece playing with her Nana’s dog

in Lusby, MD, July 2021

She’s splashed about in kiddie pools and oceans alike, although she’s still too unsure to try walking in the wet sand, more or less running headlong into the waves, as you once did.

Lizzy

Cece

Lizzy shelling in South Carolina, August 2018

Cece splashing in North Carolina, June 2021

She’s worn many of the clothes I will always think of as yours, and through the wearing, has candled a flame of your life back into these long, summer days.

Lizzy in the Chesapeake Bay, July 4, 2018

Cece in the Chesapeake Bay, August 2021

Lizzy in her shell dress at Hopsewee Plantation

in Georgetown, SC, August 2018

Cece in her shell dress at Jefferson Patterson Park

in St. Leonard, MD, August 2021

Lizzy in her crab dress, Frontier Culture Museum, Staunton, VA, July 2018

Cece in her crab dress, National Colonial Farm

at Piscataway Park, MD, July 2021

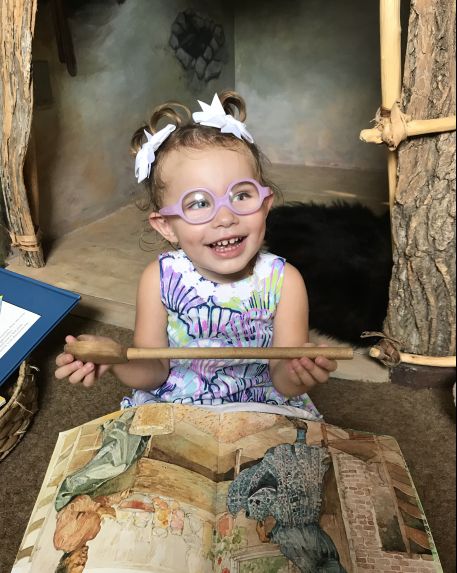

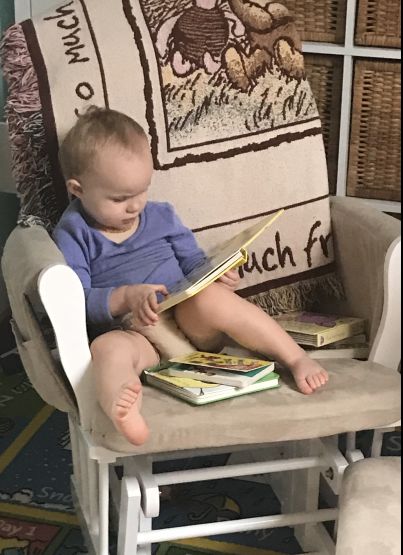

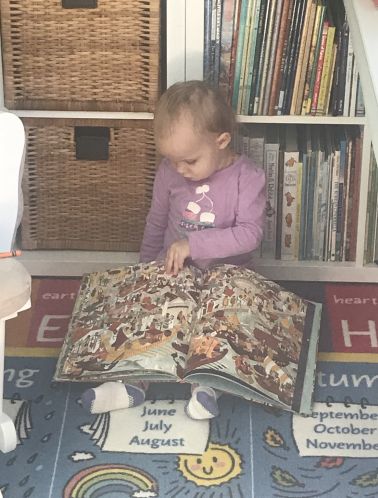

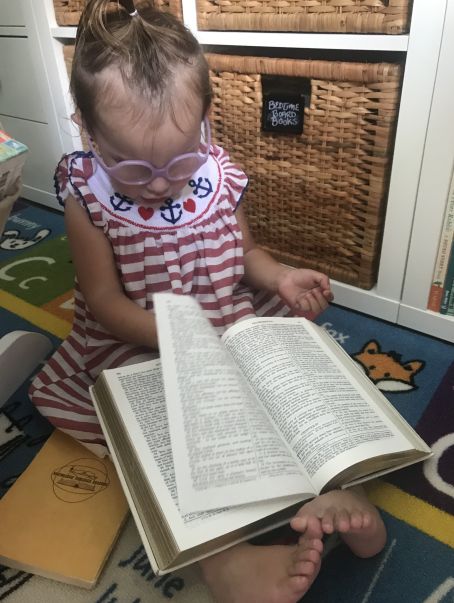

She loves books and reading more than you did, although I think a love for books was developing in you in those short months before your second birthday, and I think, given time, it would have flowered into a similar passion. But still, she sits where you sat and reads where you read, and time folds and founders, and sometimes, it’s like I can still see you there.

Lizzy

Cece

Lizzy

Cece

In some ways, you are very alike. She eats with the same piquant delight and sleeps with the same innocent abandon.

Lizzy

Cece

Lizzy

Cece

But, as alike as you are in some ways, Cecilia always has been so very different from you. This summer, I have had returned to me a toddler who says and does nearly everything that you once said and did, and yet, it is nothing like having you returned to me.

I think it is time, Lizzy. I think I’ve arrived at this amorphous destination where I was supposed to have you back in some way, shape, or form in Cecilia, and now I must grow up and acknowledge that it is not going to happen. I must sit with, accept, and integrate the understanding that you always have been, very simply, irreplaceable.

I can hear therapists and seasoned parents telling me it’s not supposed to feel the same with a second child, even if you haven’t lost your firstborn. I’m deaf to their advice, not because it’s worthless or because I disagree, but merely because I can only understand what I experience, and not what I am supposed to feel.

Lizzy and me, Spring 2018

Cece and me, June 4, 2021

Lizzy, I’m very afraid that you are irreplaceable not just in the sense that every human person is irreplaceable, but because you and I understood, wanted, and loved one another effortlessly, from the first moment I knew you existed. I think the particular soul that is you and the particular soul that is me belonged to one another without trying. There is a near superstition growing in me that what we had together should not be possible in the world of time and death, and that is exactly why time was taken from us.

Sometimes, I deliberately entertain these superstitions, wondering if the health, vitality, charisma, physical prowess, quicksilver intellect, and boundless love that embodied you was simply too much for this world–too much of what we’re aiming towards and not enough of what we lack. Perhaps there was no place for you in a world as broken as this one. Perhaps you came only to remind us of what we’re destined for, if only we could find a way to be more like you.

I’m coming to hate simple answers and reductive conclusions, and so I often dismiss these superstitions as soon as they arise. I still lack the answers to your death that I feel I need to survive, and doctors, lawyers, and loved ones alike still have little more than insubstantial condolences to offer. I’m still angry and resentful and lonely and unable to accept the unacceptable reality of your death. I still shame and punish the person that I am, knowing with a guttural guilt that Cecilia deserves a better mother than me–a mother that more closely resembles the kind of mother I once was to you.

Lizzy and me, July 2018

Cece and me, July 2021

And yet, the mother I was to you no longer exists. She died with you. And perhaps in missing you, I am also missing her–her innocence, her beatitude, and her faith. I can no more reclaim that version of myself than I can raise you from the grave. Instead, I must find a way to accept the me that is here and now and real, as I must find a way to accept Cecilia as she is and not as I wish her to be.

This means letting go of what I thought I wanted and who I was, of that which I thought I knew, and walking courageously into that which I cannot know. After all, that is how you lived your short life, and you lived it without fear. I am unable to forget the sight of you running headlong in the ocean waves, again and again. I am not as brave as you, Lizzy, but I will find a way to be brave for your little sister, who deserves every chance at life that was taken from you.

Lizzy and me, Drum Point Beach Club, July 4, 2018

Cece and me, North Caroline Aquarium

at Pine Knoll Shores, June 2021

In August of 2018, we visited South Carolina and went on a shelling cruise. You delighted yourself into exhaustion and fell asleep in my arms upon the return trip to shore. I held you and watched the water churning in frothy white behind the boat as the sunlight danced and tripped across the surface of the waves. Cecilia was growing inside of me, barely one week gestation. I was indescribably happy, although I did not yet know Cecilia existed. Still, I felt a fullness, a joy, and a completeness which now seems only a distant memory.

This past August, I took Cecilia on a day cruise to Smith Island, MD, and she too fell asleep in my arms, exhausted, on the return trip. The day was almost unbearably perfect, with the sun dancing scintillations across the horizon and the sea breezes flirting along salt-sprayed skin. I was as happy as I could be in that moment, but my happiness sat beside the emptiness that has filled me since your death, jostling for room with the anxiety and fear for Cecilia’s life that now characterize my waking consciousness.

Lizzy asleep on the return trip from a shelling cruise, Pawley’s Island, SC, August 2018

Cece asleep on the return trip from a cruise to

Smith Island, MD, August 2021

I am ashamed to admit that I cannot love Cecilia as I loved you. And yet, this is not because Cecilia is less worthy of love, nor because she and I belong less to one another. Instead, it is because I can no longer feel love or joy in Cecilia without grief and despair for you. It is not fear that restrains me; it is rather a deep and echoing knowledge that with surrendering myself to her little life, I am also accepting her suffering and eventual death. That in accepting the joy and delight and wonder of her existence, I am also accepting her limitations, her frailty, and the gossamer webbing that separates her life from her death. Her proximity to death is, I think, deeply intertwined with what and why and how she is so lovable–and so worthy of everything that I have to give.

I can no longer experience contentment, joy, or love without grief, and the ability to feel all these things at once is, I think, the knowledge of good and evil.

I have spent this summer feeling deafened by the emotional avalanche of rupturing and rebuilding family relationships, of entering the terrifying wilderness of raising a child beyond the age of two, of drowning in grief over you, over Cecilia, over who I once was, and over the emptiness my grandfather created in the lives of those he left behind. The noise has been cacophonous, overwhelming–a storm of cicada song determined to drive out everything else in its rapacious intention to consume and procreate.

But, somewhere along the way, the emotional onslaught peaked, dimmed, and withdrew. The remaining silence was strange and echoing. The dead cicadas littered the East Coast and their eggs nested across numberless trees, burgeoning with life. And in that silence, forced to sit with myself as I am and not as I once was, I began to understand.

Lizzy and me, Assateague Island, VA, August 2018

Cece and me, Osprey Beach, MD, August 2021

I cannot play guessing games as to whether or not Cecilia’s disease would have manifested in the same way without your death. I am not an epigeneticist. What I do know is that your life and your death forged me into the mother that Cecilia needs.

I spent this past Monday at Johns Hopkins Hospital, walking past patients collapsed on the floor, and waiting in rooms with other blind and disabled children. I fought our way out of procedures I didn’t believe Cecilia needed and into meetings with doctors I thought might provide better care. I crisply summarized Cecilia’s visual history, current progress, and developmental delays while simultaneously keeping her calm with books, music, hugs, and homemade apple butter.

I’ve driven five hours round-trip to obtain a two-month supply of raw goat’s milk from a Raw Milk Institute-listed farm to optimize Cecilia’s nutrition. I’ve spent hours holding her hands, helping her to sit, stand, and walk, and longer hours reading to her book after book after book. I’ve debated and negotiated with doctor after therapist after insurance agent after social security representative and mined resources from other parents of visually impaired children. I’ve spent weeks researching and detailing her medical history, completed an infant-psychotherapy home study, and enrolled us in a learning-through-play outdoor kindergarten class.

I am not the mother I was to you. I have found reserves of strength, innovation, advocacy, self-education, and discipline that were unknown to me when I mothered you. And yet, it was you that forged me into a mother. You shaped and created me into myself as you grew within my womb, rewiring my brain to forever give myself to my children. When you lived, I became who I was always meant to be, and I lived, for a time, in someplace very close to paradise. When you died, I descended into hell and had to crawl my way, bleeding, back to the land of the living to find the child I had left there.

I have become a different kind of mother for her, a mother I had no way of knowing or being when you were alive. And yet, this is the very mother that Cecilia needs–and perhaps needs simply to remain alive. This is the truth I discovered in the silence of this cicada summer. But the mystery of whether or not you needed to die in order for Cecilia to live remains.

Lizzy asleep on a beach in Sarasota, FL, September 2018

Cece asleep on a history cruise in

St. Michaels, MD, September 2021

Ah, Lizzy, there is so much that is unknown and unknowable in being human, and death is the axis upon which most of that unknowingness spins. I cannot speak words to understand my life or your death or Cecilia’s disease; I can only know, perhaps with this same knowledge of good and evil, that I am the mother Cecilia needs because you once lived.

I could not be what she needs if not for loving you, and perhaps if not for losing you. I will not say this, because I cannot know so powerful and terrible a thing. I am a mere mortal, and I accept only what is offered–your life, her life–and my purpose. And I follow the light that you remain, living and dead, the flame imperishable that guides my every choice.

I will follow you, bright angel, though the sun bleeds into a day that never rises, though the stars gutter and blink into dreamless sleep–I will follow you. When everything is lost, and I cannot see my way, yours is the single light that will remain.

Although time continues to pass and the world moves faster, I still hold you in my arms, feeling you breathe against my chest, watching a dimming day descend over the ocean, and wonder at the gift that is your life–my precious baby, my radiant saint.

With every breath, I breathe my love for you,

Mama

I love the assortment of pictures, comparing and contrasting those of Lizzy and those of Cece. Although it was difficult for you to write, I am glad you have now articulated the hidden feelings and fears that plague us all. Please do the world a favor and keep writing and inspiring us all.