Tomorrow

Mightier than Este is Nienna, sister of the Feanturi; she dwells alone. She is acquainted with grief, and mourns for every wound that Arda has suffered in the marring of Melkor. So great was her sorrow, as the Music unfolded, that her song turned to lamentation long before its end, and the sound of mourning was woven into the themes of the World before it began. But she does not weep for herself; and those who hearken to her learn pity, and endurance in hope. Her halls are west of West, upon the borders of the world; and she comes seldom to the city of Valimar where all is glad. She goes rather to the halls of Mandos, which are near to her own; and all those who wait in Mandos cry to her, for she brings strength to the spirit and turns sorrow to wisdom. The windows of her house look outward from the walls of the world.

– J.R.R. Tolkien, “Valaquenta,” The Silmarillion, 28.

What does it mean to be “acquainted with grief?” Isaiah 53:3 speaks of a “man of suffering, knowing pain,” which many Christians interpret as a foreshadowing of Christ. Does this mean that we need to suffer physically and psychologically like Christ in order to know grief? Is it actually necessary to encounter a personal tragedy in order to acquaint oneself with grief? Or is it just woven into the very fabric of what it means to be human?

Tolkien himself was acquainted with grief; orphaned by the age of 12, he went on to watch his best friends from childhood bleed to death in the muddy pits of World War I. Much of his writing is deeply occupied with suffering and death, and grief plays a major role in his work, so much so that one of the gods (Valar) of Middle Earth exists for the explicit purpose of grieving.

I find myself wondering these days if love is actually possible without grief. Arguably, this does a grave injustice to the many amazing parents who have never lost their children and yet have loved their children deeply and forever. No, I think it’s more complicated than that. I think that because suffering and death are built into the very framework of what human existence means; by extension, the omnipresent threat of grief and loss is what causes us to love the way we do. Without the ubiquitous shadow of possible loss, we could not love with the same selflessness. Ultimately, death is so much bigger than we are that all we can do in the face of it is offer everything that we are. This requires nothing less than a total surrender of self to the other: rather, to the beloved.

What does it mean that one of the world’s best writers felt that grief was so inherent to the human experience that it necessitated the endless focus and attention of an entire deity? And what do we mortals, who can only grieve so much for so long without needing to go on with the tedious processes of the flesh (feeding, drinking, urination, defecation, sleep, etc.), do when we have to stop grieving in order to continue the work of prolonging our own lives or the lives of others we love? At what point do we surrender not only to the beloved but also to our helplessness to continue running on the hamster wheel of human existence?

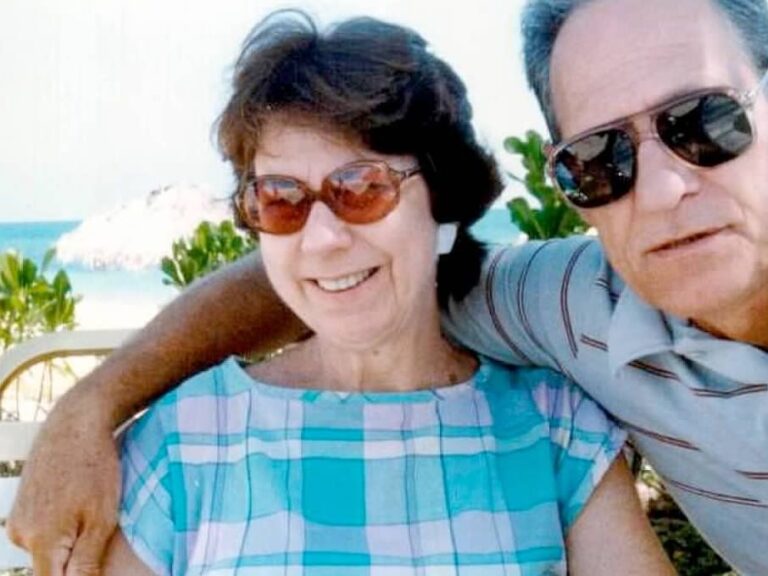

Tomorrow, it will be 365 days since Lizzy died, and my grief still centers around the conviction that she should not have died so young. But isn’t there an argument to be made that she died before she ever had to learn about the cruelty and horror that is present in the world? Before she ever had to undergo any sustained, long-term mental or physical suffering? Before she had to watch someone she loved suffer and die? Isn’t there an argument to be made that if there is a heaven, dragging Lizzy out of it to come back to this cesspit of despair and desolation would be the epitome of selfishness? Isn’t there an argument to be made that human existence is so fragile and so diseased that life itself is not worth fighting for?

Yes, Caroline, you will say. That’s the suicide bomber’s and the school shooter’s argument. Is that really where you’re going?

No, it’s not where I’m going, but it is a question that goes through my head. There are times that I feel with perfect certainty that my grief is actually senseless because it is predicated on the fact that I believe that Lizzy would have been better off alive. However, I don’t actually know this to be true. Would Lizzy have lived to die of cancer or to be raped or murdered or to commit suicide? Would the darkness of this world have eventually consumed her like it does so many others? Where do I actually get off believing that Lizzy should have lived when living itself is so fraught with misery and desolation?

One of the first stories I read on the Compassionate Friends website was the story of a 22-month old who was murdered in her bedroom. Over 20 years later, the parents had nothing more to say other than that they were still numb. After all, what can you say when Elie Wiesel recounts seeing babies thrown into the air to be used as target practice? Or when you hear about the countless thousands of mothers in Rwanda who had their nursing infants ripped from their arms, dashed to death against boulders, and who were then raped and hacked to pieces with machetes? What do you say when you hear stories about a 4 month-old admitted to the hospital because he almost died from suffocation, and then hidden cameras reveal the parent of that baby sneaking in with a pillow to finish the infant off? How do you explain the infants who are sexually abused? Or those babies with sunken eyes and countable ribs that are starving to death in impoverished countries because their mothers have been told by doctors not to breastfeed, and yet they cannot afford the cost of formula? Are there words for the suffering of the babies who are partially born only for the express purpose of vacuuming out their brains until their skulls collapse?

And would the babies who are bodily vacuumed out of their mother’s uterus make a sound if only anyone could hear them?

What does it say about the human race that we target the most fragile and vulnerable among us for violence and eradication? Who can see the huge eyes, tiny, chubby arms, and miniature fingers of a seven-month old girl and yet shake her into irreversible brain damage because she wouldn’t stop crying? What is it about our species that instead of safeguarding and treasuring the very young and the very old, we consider them to be disposable inconveniences? Why is it always the youngest and the oldest among us who are killed first?

These questions spin like knives through my head. Do you have answers for me? How can anyone say, with perfect confidence, that we are better off living than we are dead?

The truth is that we simply do not know.

I confess I cannot escape this question. Life is work and suffering and death. There is simply no argument that will make me feel this statement is untrue.

For the past few days, I keep flashing back to Lizzy’s burial, to lying beside her open grave, staring at the white petals littering her white coffin, and wanting to throw myself. I think about how I spent the rest of that day trying to persuade my sisters to anesthetize me, take Cecilia out by c-section, and then euthanize me. I remember what I said, and I remember what I felt, and I feel only pity for who I was and shame.

What a coward I was. What sort of explanation would my sisters have had to give Cecilia? “Your mother valued your sister’s life over yours and over her own”? “Your mother couldn’t find it in herself to cope with her own pain for your sake”? These statements would have been perfectly true. It would have been the coward’s way out. It’s absolutely harder to stay here without Lizzy.

I am no longer capable of feeling guilt that I get to live when Lizzy was chosen for death. This is because I no longer believe that I have received something “better” than Lizzy in remaining alive. Being here, on this planet, in this body, in this place–is hard–so much harder than taking a pill or a bullet or a shot and ending it all. A year ago, it required enormous effort to just get through the minutes–and sometimes even the seconds–without collapsing and wanting to give up. Now, I still force myself to work and suffer through the minutes and the hours and the days. I am just better at it than I was then.

It is work to remain alive, not only because part of me will always wish I could die in order to be with Lizzy, but also because safeguarding and treasuring Cecilia’s life is an enormous amount of work. It is work because memories of Lizzy are crippling and sometimes, convincing myself to keep going requires discipline and endurance. But it is also work because Lizzy’s death taught me that I have no option but to make every single second that I am alive matter. As long as life still remains within me and within Cecilia, there is work to be done, and what I want for myself or what I wish was different is of little importance.

Minute by minute has passed as I have written this post. Minute by minute will continue to pass as the clock nears midnight, and then I will have to face tomorrow’s minutes. I will not be writing a post tomorrow. There are some things that are beyond words, and lying down next to your two-year old while they turn off the life support machine is one of those things. Tomorrow, I will nurse and feed and play with and read to Cecilia and wonder how to explain to her one day why April 5 is so hard for Mommy. And the minutes will pass, and the day will be over, and then I will find words again.

Until then, there is nothing else to say.